| pages_with_pdfs_watkins_article.pages | |

| File Size: | 34404 kb |

| File Type: | pages |

Ancient Stones, Ritual Space and the Curve of the Land

|

When we feel disconnected from the land, we feel unhappy - even if we don’t consciously realize it. When we hear about the toll our presence is taking on the earth - the pollution of its air, soil and waters, the extinction of species - we cannot bear it. So we often do one of several things: deny it, cover our ears, protest and/or try to live more sustainably by recycling, reducing our carbon footprint and buying local or organic produce. But even if we make these attempts, we wonder if they aren’t all too little, too late.

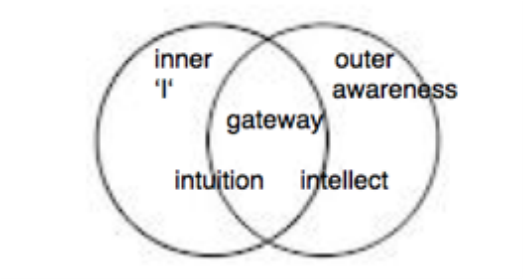

My new novel, The Curve of the Land, is set in 1980’s Britain when environmental crises were becoming more widely reported, thanks to activist groups like Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth and the Soil Association. The hunting of whales, the burning of the rain forests, the spread of chemical pollutants were the headliners, but there were legions more problems. In Britain the implacable advance of sprawl and motorway construction through untouched countryside combined with modern farming practices that tore out miles of hedgerows seemed to be swallowing up a way of life. Here is how Philip Larkin put it: ‘And that will be England gone, The shadows, the meadows, the lanes, The guildhalls, the carved choirs. There’ll be books; it will linger on In galleries; but all that remains For us will be concrete and tires.’ Like many others, I was acutely aware of these issues and struggled with a sense of powerlessness and guilt about my own lifestyle. But I also struggled with something else, which was how to apply what I knew about our deeper nature to these problems and our response to them. From the age of 18, I had known that we human beings are hosts to a powerful force. One evening while sitting having tea with friends, I suddenly (and for no apparent reason) felt an energy building inside me. A light-filled power was welling up, like a great golden sun, blazing into my body and mind. Instantly I recognized that this brimming force was what is meant by the word love. And it was who I really was, who everyone really was. Many years later, I found a poem by W B Yeats, that describes a similar transfiguration, only instead of having tea at a friend’s, he was sitting in a London cafe: ‘While on the shop and street I gazed My body for a moment blazed, And twenty minutes, more or less, It seemed so great my happiness, That I was blessed, and could bless.’ The experience of ‘blazing’ was visceral and resonated throughout my memory and into the future. Implications tumbled into my mind and continued after the light subsided. I saw that even though the same energy resides in every human being, most remain oblivious of it. And yet if we lived more directly from it, society would be utterly transformed. It was as if I looked down the long lonely often anguished history of people living out their lives without ever feeling fully their own irrepressible power and realized that most of our problems stemmed from this one, almost unbelievable condition of amnesia. Did the pollution in the oceans and air and earth mirror the pollution in our own consciousness - the fears and bitternesses that obscure the connection to that deeper vein of ourselves? If we knew that we were ‘blessed’, as Yeats did, could we not then bless the land, and one another, and work things out quite differently? Britain has or had a strong ‘establishment’ mentality, but it is also a nation of eccentric subcultures. One subculture that was also coming to prominence during the 1980’s was a renewed interest in Britain’s neolithic heritage: the ancient stone circles, (Stonehenge being the most famous), standing stones and dolmen that are so plentiful, particularly in the western part of Britain. Research into their site plans and construction showed how deliberately aligned they are with other features of the landscape, as well as with key positions of the sun and moon, (again, the most well known example is the midsummer sunrise touching Stonehenge’s Heel Stone). Additionally, the stones are mostly granite which has piezo-electric properties that some believe affect consciousness. Taken together, the findings led to speculation that the sites had served shamanic purposes, built to heighten the connection between our psyche and the earth itself. Intriguingly, D H Lawrence evolved similar ideas about the affect on consciousness of stones found on the moors above Zennor, a village in the far west of Cornwall where he lived in 1915: ‘This development in Lawrence’s thinking is indicated by his letters from Cornwall and his ,,, writing in which he suggests that the landscape there has the power, concentrated in its rocks, to alter consciousness ..’ from ‘Lawrence’s “Best Adventure”: Blood-Consciousness and Cornwall’ by Jane Costin In the semi-autobiographical novel “Kangaroo’, Lawrence wrote: ‘Cornwall is a country that makes a man psychic. The longer he stayed, the more intensely it had that effect on Somers. It was as if he were developing second sight, and second hearing. He would go out into the blackness of night and listen to the blackness, and call, call softly, for the spirits, the presences he felt coming downhill from the moors in the night.' Cornwall is the south west peninsula of Britain and its geology is mostly granite. Unspoilt beaches and a warm climate (if it isn’t raining) make it a popular holiday destination for families, including mine. So I have childhood memories of wide firm stretches of sand, echoey, dripping caves and rock pools deep enough to wade in. A couple of teenage summers were spent on the North Coast, mesmerized by the surf’s green walls, and later on again I got to know the wild resonance of West Penwith, which is the northern half of Cornwall’s claw foot. This is the area where the village of Zennor lies and where a high concentration of dolmen and stone circles are found. When I visit Cornwall I feel the sense of home-coming that all places we know well hold for us. But there is also an excitement at entering a land where I may be granted return to the freedom of a different order of awareness, a sacred space that is familiar but not ordinary. All these strands are woven into ‘The Curve of the Land’. I knew there was a connection between ourselves and the land, the oceans, the wind. I wondered if the connection didn’t move both ways. I wanted to explore the possibility that we could take care of the planet in ways that didn’t end up burning ourselves out in anger and futility. The main character, Jessica, works for Friends of the Earth. Her boyfriend, Paul, formerly a fashion photographer, now shoots environmental features and is becoming more zealous than Jessica herself, who is wearying from the fight. At the same time, she is wanting to return to a deeper, more intuitive, less rational place in herself, a place that she feels she has censored in their relationship. After a row with Paul, Jessica decides to join a tour of the ancient sites in western Britain, without him. The ancient stones sit there on the landscape like so many presences, gateways, possibilities. Of course they are no more ancient than other natural formations of the hills and cliffs, but the fact that they have been manoeuvered into relationship with the surrounding land and the movements of the cosmos links our awareness across dizzying expanses of time to others who have gone before us. What did those people know then, that we now do not? Did the builders have a sensitivity not just to the tilting, rotating dance of the planet and its moon, but to a deeper field, to Gaia? How did the blue stones, sourced in South Wales, travel the160 miles to Salisbury Plain? How did they lift that 30 ton capstone onto the four upright slabs of the dolmen? And what changes have these stones, viewed now as part of a farmer’s field, or a feature of the National Trust’s coastal walk, what have they seen? What do they know about forests coming and going? About climate change, glaciers, waters rising and falling? About tribal customs and beliefs? About the buried gold of the roaming Celts? I wanted to write a literary novel, but not a narrowly ‘realistic’ one. Our contemporary ‘realism’ is part of the way we wall ourselves off from experiencing our deeper power. If we cannot watch something through a microscope, it doesn’t exist. That’s why many accept the idea that we are just a complex aggregate of cells, brought to life by chemical firings in the brain and nervous system. The social sciences, including psychology, take their cue from this biological-machine model and view human beings as shaped almost entirely by the nature and nurture ingredients allotted to them. The literary outcome of this literal-mindedness is that very few characters are drawn with any interior, unquantifiable spark to them. Instead at best they are sophisticated players or less able victims in a complex but random shuffle for survival; or at worst, caricatures swashbuckling through plots of predictable melodrama, as the dead horses of motivation are whipped by more and more extreme situations to try to get them to stand on their hooves again. The stones rear up out of smooth grass, like so many rents in the veil of our own awareness. In ‘The Curve of the Land’ they act as a metaphor for the mystery of ourselves, and the potential of a more intuitive connection to earth. Part of the way I explore this idea is through the main character’s experience of shamanic descent, in which place and time trail off into a different dimension, but one which is woven into consciousness itself. Both in my novel, and in actual time and space, the ancient stones hold the power of place and placement. They form ritual space that draws us into a deeper level of ourselves. Visionary architect Christopher Alexander writes about the power of place, and of art, to do this: '...the ultimate questions of architecture and art concern some connection of incalculable depth, between made work (building, painting, ornament, street) and the inner "I" which each of us experiences. What I call "the I" is that interior element in a work of art, which makes one feel related to it. It may occur in a leaf, or in a picture, in a house, in a wave, even in a grain of sand, or in an ornament. It is not ego. It is not me. It is not individual at all, having to do with me, or you. It is humble, and enormous: that thing in common which each one of us has in us.... For I believe ... that the thing I call the I, which lives at the core of our experience, is a real thing, existing in all matter, beyond ourselves, and that we must understand it this way in order to make sense of living structure, of buildings, of art, and of our place in the world.’ ‘Luminous Ground’ When we find ourselves in places, whether man-made, or natural, or a bit of both (as ancient landscapes often are) that causes the sense of connection to line up between the essence of that place or object, and the essence of ourselves, it is like a gateway opening. An entrance - to what? There are many stories of finding caves, hollows in old trees, toadstool rings that turn out to be en-‘trances’ to fairyland or the otherworld. The Celts had the notion of ‘thin places’ which were places or times, such as marshes, dusk, changes of season, when two elements overlapped, thinning out the barriers between the worlds so that a way opens between them. I wrote a series of sonnets called ‘Between Two Worlds’ exploring some of these ideas. Here is one of them: Thin Places Each morning what is familiar is seen again, as we awaken out of night and our part of Earth spins round into light - that day-shift still traveling while they dream. Continents, neighbourhoods striped in darkness and sunlight, oceans tilted warm then cold - it is this interchange that grows the world, makes the soft grey overlap that stretches out the dusk, the mist that blurs the morning land. Thin places, the Celts said, where the deep bleeds through and shifts the hardened shape of things, a clearing like the night that mimics sleep. This is the world riddle that we answer when we see one depth within the other. To me the resonance between ourselves and a place or object is like that gateway or thinning which opens a way in us to depth and possibility. We leave the world of our old certainties, and enter the fertile realm of imagination In other words, at the very moment we are transfixed by this connection to a place or object, we also feel an expansion, a lifting up and out from our old ways of relating to the dimensional world. We are no longer embedded in our expectations or needs or demands of it. The same applies to our relationships with people. What this sense of liberation means is that the full circuitry of our own consciousness is opening up. Buddhists call this expansion of consciousness the emergence of intuitive mind, which they describe as the overlap between two levels of self and awareness. I use the ancient shape of the ‘vesica piscis‘ to depict this expansion. (See diagram on the side.) The ‘vesica‘ symbol is created when the circumferences of two equal circles intersect each other’s center. The root shape of sacred geometry, it encodes proportions that govern the growth patterns of nature, making it an apt symbol of the matrix of intuitive mind. The overlap between our inner and outer awareness opens a gateway to depth, and frees a flow of thought, informed by both intuition and intellectual analysis, that is generative. The insights we come up with, formed from the full circuitry of consciousness as they are, will, like appleseeds from the apple tree, contain the same life-enhancing potential. They will develop into ideas and then into actions and projects that are nourishing, workable and in sync with the wider ecosystems of the planet. The world and our consciousness are blended together. I believe the builders of the megaliths understood this better than we do today. The same understanding underlies most sacred traditions and myths but is, in my view, expressed most explicitly by the Grail myth, which features a King who, because he is wounded, presides over a Wasteland Kingdom. The crops fail, the cattle cannot reproduce, and the land is ravaged by war and conflict. These wasteland conditions are all reflections of the King’s wound because the King and the land are one. Our present-day ecological crises, as well as the wars that exacerbate them, are reflections of our own wound of separation from the life-giving power of our real selves. In the Grail myth, the Wasteland Kingdom will only be restored when the Wounded King is healed, and the same possibility stares back at us still. We can restore the wasteland when we free up the flow of energy and inspiration inside us. |